"History never repeats itself, but the Kaleidoscopic combinations of the pictured present often seem to be constructed out of the broken fragments of antique legends."

- Mark Twain

***Disclaimer: Nothing in this blog post should be construed as personal financial advice. Do your own homework. If you want advice, hire a pro. This blog post is for entertainment purposes only.***

Once upon a time, back in early March of 2007, something very interesting happened.

The financial news channel CNBC ran its inaugural Million Dollar Portfolio Challenge, a stock market contest that anyone could enter for free and potentially go on to win a million bucks. Naturally, lots of people, including yours truly, signed up to play.

The first day of the contest was March 5th, a Monday. That was also the first day that traders could trade on the news from the weekend, news that had broken after the close of the previous Friday's trading session. One piece of such news was about a mortgage company called New Century.

Monday's stock market action saw New Century's stock lose somewhere in the neighborhood of 60% of its value. (I'm going by memory here, so don't quote me on that percentage.)

The smart contestants went all in on New Century on the expectation that it would have a dead-cat bounce the following day. Indeed, that's what happened. New Century's stock price was up something like 25 or 30% the next day. Those contestants who loaded up on it leapfrogged ahead of the rest of the pack. The contest was ten weeks long, but the outcome was mostly decided on day one.

Needless to say, I was not one of those smart contestants. I didn't pile into New Century that day, nor did I go on to win the million bucks. However, one very important thing happened as a result of those first two days of the contest: I became aware of the subprime crisis. I began looking into it and keeping an eye on events. I quickly began to realize that the whole financial system was on the brink of utter collapse.

Obviously, it didn't collapse. There was some pain in in 2007-2009, to be sure, but not nearly as much as I expected. Basically, all the doom-and-gloom stuff I had read about had affected my mind to the point that I was essentially caught up in a mania. (Years later, when everything settled down and I was able to rationally evaluate everything, I was embarrassed and ashamed about how panicked and irrational I'd become. I swore then that I'd never let myself get swept up in a mania again. This experience would come in handy during the whole Covid thing, a mania in which many people are still firmly and unfortunately enthralled but in which I kept a pretty reasonable head throughout.)

The reason I bring all this up is because of the recent troubles suffered by Silicon Valley Bank and some other similarly-oriented banks. It's all eerily familiar. History isn't repeating itself, but as Mark Twain suggested, those broken fragments of 2000s-era legends are reconstituting themselves into a present-day reality.

So let's go over some of the similarities and differences, compare and contrast, and see what truths, if any, can be wrung from the whole mess.

From tech to real estate

After the bursting of the tech bubble at the turn of the century, investors looked for a new place to put their money to work. The Federal Reserve had already come to the rescue by lowering rates to nearly nothing, and now it was the government's turn to join in. Specifically, Bush's "home ownership initiative" and the resulting regulatory framework. Let's take a look at what it entailed:

- The US homeownership rate reached a record 69.2 percent in the second quarter

of 2004.

The number of homeowners in the United States reached 73.4 million, the most ever. And for

the first time, the majority of minority Americans own their own homes.

- The President set a goal to increase the number of minority homeowners by 5.5

million

families by the end of the decade. Through his homeownership challenge, the President

called on the private sector to help in this effort. More than two dozen companies and

organizations have made commitments to increase minority homeownership - including pledges

to provide more than $1.1 trillion in mortgage purchases for minority homebuyers this

decade.

- President Bush signed the $200 million-per-year American Dream Downpayment

Act which will

help approximately 40,000 families each year with their downpayment and closing costs.

- The Administration proposed the Zero-Downpayment Initiative to allow the

Federal Housing

Administration to insure mortgages for first-time homebuyers without a downpayment.

Projections indicate this could generate over 150,000 new homeowners in the first year

alone.

- President Bush proposed a new Single Family Affordable Housing Tax Credit to

increase the

supply of affordable homes.

- The President has proposed to more than double funding for the Self-Help

Homeownership

Opportunity Program (SHOP), where government and non-profit organizations work closely

together to increase homeownership opportunities.

- The President proposed $2.7 billion in USDA home loan guarantees to support rural

homeownership and $1.1 billion in direct loans for low-income borrowers unable to secure a

mortgage through a conventional lender. These loans are expected to provide 42,800

homeownership opportunities to rural families across America.

At the time, this all sounded like good news. It gave everyone the warm-and-fuzzies. Well, almost everyone. Congressman Ron Paul objected:

H.R. 1276 takes resources away from private citizens,

through confiscatory taxation, and uses them for the

politically favored cause of expanding home ownership.

Government subsidization of housing leads to an excessive

allocation of resources to the housing market. Thus, thanks to

government policy, resources that would have been devoted to

education, transportation, or some other good desired by

consumers, will instead be devoted to housing. Proponents of

this bill ignore the socially beneficial uses the monies

devoted to housing might have been put to had those resources

been left in the hands of private citizens.

See that part about "excessive allocation of resources to the housing market"? He's predicting a real estate bubble. This wasn't the only time he would make that prediction. There was plenty of early warning, and not just from Ron Paul, that a real estate bubble was forming. Those warnings were simply ignored. People preferred to believe that real estate prices always go up, and they made financial decisions based on that belief.

Reading through Bush's total initiative, it's easy to see how the bubble was inflated. The government essentially told lenders that they had to lend to anyone with a pulse or else they'd be punished. Lenders didn't want to be punished, so they gave out loans without regard to ability to repay. The federal government forced malinvestment into the real estate market.

In 2004, the Federal Reserve began raising rates, and that was the beginning of the end.

It would take a couple of years for the results of those rate hikes

to percolate through the system, but there was no stopping things now.

It particularly affected those with adjustable-rate mortgages, and over 90% of subprime borrowers in 2006 had ARMs. Defaults were inevitable.

The

collapse became apparent in 2006 when real estate prices peaked. Fast

profits made from "house flipping" were no longer easily available. The

music had stopped, and everyone was suddenly scrambling for a chair.

So, just as the tech bubble of the 1990s had been inflated by easy credit and malinvestment and then just as quickly popped, so now the real estate market was going to suffer the same fate. This time, though, the contagion would spread to the banks. This resulted in the financial crisis of 2008-2009.

The stock market

Now, let's see how this affected the broader stock market. Here's the chart for the S&P 500.

As you can see, the market kept going up until late 2007. The decline in real estate prices had already been going on for a year, and the collapse of New Century had happened months earlier. In fact, those first few dead canaries in the coal mine didn't really affect the stock market much at all. There was a big drop off in late February of 2007, but that was due to a 9% drop in the Chinese stock market the night before, not anything related to the American real estate market.

There was a brief correction and consolidation, but by mid-April, the market was making new highs.

Everything was going to turn out okay, right? Well, not so much. That summer, there were other signs that things weren't quite right. There was a hard correction in late July and early August, but then the market headed back up and again made new highs. It peaked in October.

Then it began its long decline, not bottoming out until March of 2009, two years after the big New Century stock price crash.

The Federal Reserve lowered rates the whole way through the financial crisis, trying to soften the blow, but it didn't help. The damage was already done, and any easy money would now only fuel the next bubble, not re-inflate the previous one.

The main point of all this, the one thing that is essential to understand, is that there was a significant time lag between the various stages of the collapse. A nation's economy is a big ship, and it takes a long time for that ship to change course, even when the change is inevitable. There can easily be conflicting signals in the interim.

And that brings us back to the present and current issues. The stock market of 2023 might go up for the next few months, but don't let that lull you into thinking that Silicon Valley Bank and all the other dead canaries in the coal mine didn't amount to anything substantial. Keep the time lag in mind.

Inflation and the petrodollar

The financial crisis of 2008-2009 spurred the federal government to engage in some overtly inflationary measures. There was plenty of outcry about this at the time. Those critics said the politicians were just kicking the can down the road, making the inevitable comeuppance even more drastic when it would eventually arrive. Those critics weren't ignored; they were shouted down on national television. It was a crazy time, and there was outright panic.

So the government threw tons of money at the problem, the Federal Reserve kept rates close to zero, and everyone who identified with Hayek more than Keynes waited for the inflation to take root and grow into a tree made of Weimar Papiermarks.

Throughout the whole saga, though, there was one thing working in favor of the dollar's strength, and that was its role as the world's reserve currency.

Since 1974, the dollar has been quasi-backed by oil. We call this arrangement "the petrodollar." I don't want to wade into too much nitty-gritty, so I'll just stick to the salient points. Oil since the 1970s has been sold exclusively in dollars, and since the whole world needed oil, it also needed dollars in order to purchase that oil, and that provided the dollar with a demand floor that it wouldn't otherwise have had.

There have been a few occasions where an oil-exporting country has tried to rebel against this arrangement by selling or threatening to sell its oil in some other currency. Those occasions are coincidentally--or not--often followed by regime change instigated by the U.S. government. The message, even if just implied rather than stated outright, is nevertheless clear: if you sell oil on the global market, you'd better give Uncle Sam his cut.

So long as the U.S. military remained the dominant force on the planet, the government could coerce the whole world into the petrodollar arrangement. And as long as the dollar was a half-decent investment vehicle anyway, and at least as good as any other currency, it wasn't that much of a burden to be forced to use it. Both the carrot and the stick were in play here.

But what if the world lost its fear of the U.S. military? And what if, at the same time, the government weaponized the dollar in a way that severely spooked other governments and caused them to lose faith in the safety of their dollar-denominated investments? What if there's no longer either a carrot or a stick?

This is the "You are here" moment in the timeline.

Between the "helicopter leaving Saigon" moment from Afghanistan, the Ukrainian bluff being called by Russia, the U.S. military's lower recruiting standards and missed recruiting goals, and various other humiliations, the world has lost a lot of its fear of the American war machine. At the same time, the weaponization of the SWIFT system and the seizure of Russian assets has made the world wary of leaving any wealth in a place or format where the U.S. government can make it disappear on a whim.

The result, as we're seeing now in real time, is global de-dollarization. Here are a few examples from the past few months:

When these countries reduce the amount of trade they perform in dollars, then they reduce their need to own dollars. Add in the uncertainty and risk involved with holding a currency that has been weaponized, and it's no surprise that other countries are now dropping dollars like they're hot potatoes.

So where do those dollars go now? They go to the only place they're still needed. They come home. They get repatriated into the American economy. The result, as one might easily guess, is a non-trivial amount of inflation.

These inflated dollars, by the way, include Treasury bonds. About ten percent of all U.S. Treasury debt owned by foreign governments was dumped in 2022.

https://ticdata.treasury.gov/Publish/mfh.txt

Surely hyperinflation is just a stone's throw away, right? We're all going to be wallpapering our homes with Benjamins, right?

Well, not so fast...

A challenger appears

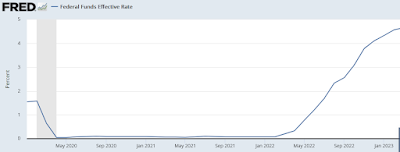

The Federal Reserve, led by Jay Powell, has been increasing interest rates in recent months. Pretty steeply, too. Jay Powell is apparently channeling his inner Paul Volcker in an effort to combat inflation.

Such a rapid rise in rates will be felt the most in sectors of the economy that are very rate-sensitive.

Like banks.

And that's exactly what we've seen with the recent bank collapses in California.

I suspect Jay Powell will continue to raise rates so long as inflationary forces--by which I mainly mean global de-dollarization forces--continue to be a factor.

If we see the same time lag we saw in 2007-2009, then we can expect to see major banks--not just small, local ones--eliminate departments and positions, fire senior executives, beg for loans, and so on and so forth during the remainder of the year. We might see a bankruptcy or a buyout.

However, I think things might occur faster this time. Remember, back in 2007 and 2008, the Fed was lowering interest rates as the financial crisis unfolded. This time, I don't think that will happen. I think rates will continue to rise, and I think that will accelerate the big crunch of the financial sector.

There was a lag of a year and a half between the collapse of New Century and the collapse of Lehman Brothers. I don't think today's big banks--the ones that are vulnerable, I mean--have that long. I think they have a year or less. Since stock market crashes like to happen in the early autumn, I'd place my bets on a September or October collapse.

Bread and circuses

Naturally, few people are talking about any of this stuff. There are sports events to watch, politicians to rage about, and all sorts of other distractions. Economics is boring. The dollar is the world's reserve currency, and it's been that way for a long time. The experts say nothing will change any time soon, so why worry?

That's the problem with major paradigm shifts. Normalcy bias results in few people recognizing--and even fewer admitting--that the shift is actually happening. If the sun has risen in the east every day of your life, then you expect it to continue to do so for every subsequent day... until one day when you find yourself at the north pole in the middle of winter and the sun doesn't rise at all, and then your whole worldview is shaken to its core. Suddenly, the sun rising in the east isn't a permanent part of the human experience but rather a subjective thing wholly dependent on spherical geometry.

The popular phrase "banality of evil" refers to people who engage in evil deeds in a rote, workmanlike, dispassionate way. We're seeing the same banality right now with regards to this monetary paradigm shift. Very few people are treating the situation with the gravity it deserves, least of all the major media organizations who should be sounding the alarm the loudest.

As for regular folks, they're just going about their lives. They're watching their favorite shows and taking their kids to ball games. They're grilling out and ordering stuff on Amazon. They simply don't care much about all this bank stuff. And frankly, they shouldn't have to. They didn't vote for or otherwise demand all the bad policies that got us into this mess. It's not their fault.

Fault or no fault, though, here we are. We are on the cusp of a paradigm shift in how the world economy works. Unless something radical happens to jar us off the current path, the petrodollar is on the way out, and a good chunk of America's wealth will go with it.

Conclusion

I'm reluctant to make predictions about this stuff. There are too many unknowns.

It's entirely possible that Jay Powell's hawkishness on rates will save the dollar and cause all the Damoclean swords to simply evaporate.

It's also possible that the Fed's efforts won't be enough and we'll be using wheelbarrows full of cash to buy our groceries.

It's also possible that the government will take advantage of dollar instability to force us to use a CBDC.

It's also possible that the government will erroneously conclude that getting into WWII saved the American economy in the 1940s, therefore getting into a major war in 2023 is just the solution to our problems. We're already seeing all sorts of belligerent talk from politicians on both sides of the aisle. The prospect of a global war is the biggest wild card of all.

However things shake out, I don't think we'll avoid a stock market crash within the next year and a half. Keep a close eye on your stops, and be ready to buy stuff on sale after the crash. If you keep a cool head and plan wisely, you might still come out of this okay. Fortunes were made during the Great Depression, you know. All it takes is enough guts to run against the herd. If you had loaded up on stocks in March of 2009, then you would have made out like a bandit.

To paraphrase R.E.M., it's the end of dollar hegemony as we know it, and those of us who are diversified outside the dollar and ready to buy stocks at deep discounts after the crash feel fine. :D